Copyright laws are threatening to shut down the Internet. But NFTs could prevent that happens.

¿Are there ways to provide economical benefits to authors and artists, without appealing to copyright infringement litigation?

Pay for the content? or pay to Artist?

Since the beginning of the Internet, media companies have been worried about the losing of value from their productions, due to the uncontrollable distribution of copies in the digital world.

These media companies have adopted the mindset of consumption-based business model where people pays for accessing the digital content. They believe that the commercial value of intellectual works is related to the scarcity of copies.

But the performance of NFT market has been demonstrated that restricting the access to digital creations is no longer needed for generating revenue to artists. The motivations that drive people o invest in tokens from an NFT project aren't necessary linked to the consumption of the digital goods represented in the NFTs metadata, but is more related to a Bonding with the original Artist.

What makes this blockchain technology more revolutionary, is that such Bonding becomes an Store of Value that can be traded in markets. In that way, collectors support the artists work, and at the same time encourages the free digital distribution of the art pieces.

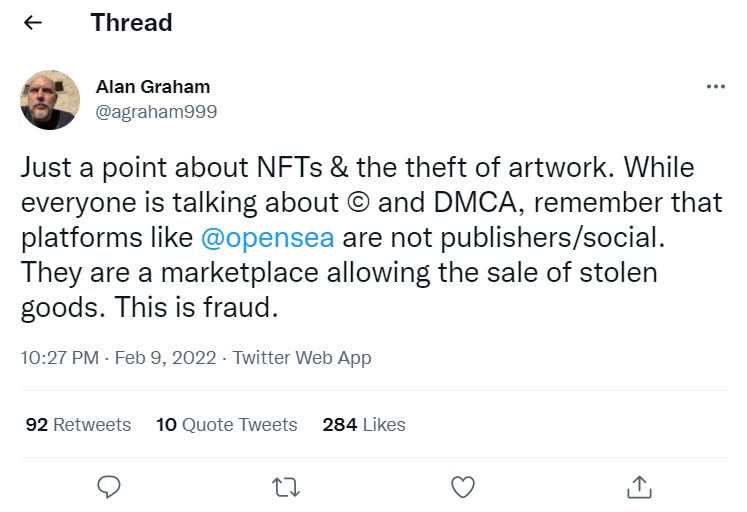

However, such technology cannot prevent that unscrupulous actors commit plagiarism or impersonate artists with fake accounts. Due to their unrestricted and decentralized nature, open platforms like OpenSea and Rarible have been overcrowded with too many copyright infringement complains. [1] In a public announcement from its official Twitter account, OpenSea, the world’s largest decentralized marketplace, has revealed that more than 80% of the “free” NFTs minted on the platform were plagiarized, fake or spam.

Legal Shield for Web Platforms

Until now, the best legal mechanism that online platforms already have for dealing with user-generated content is the DMCA framework, which protects them from potential litigation caused by copyright infringement from their users. It has allowed social networks like Facebook or Youtube to alleviate conflicts between offenders and plaintiffs, by following the due diligence of notification and elimination of the illicit content. In that way, web companies have avoided paying millionaire indemnifications. [2]

Such a legal mechanism was developed by the US Congress between 1996 and 1998, in response to numerous legal conflicts that were unleashing with the appearance of the Internet and the World Wide Web. With an amendment to the United States Communications Decency Act, Section 230, Congress provided legal protection to Internet companies from costly litigation for violations committed by users who upload content, as long as they take the necessary steps to prevent such violations. [3]

Were it not for the legal mechanism established by the DMCA and Section 230, no Internet company would have survived the 2000s, and we wouldn't have the applications that the Web has given us and that we still use on a daily basis, such as most popular social networks. The Internet just would cease to exist.

Still, media publishers and record label associations claim that the DMCA mechanism does not provide enough protection for their works from online media piracy. In a publication by the Center for the Protection of Intellectual Property (CPIP), Professor Bruce Boyden exposed a report on the ineffectiveness of the DMCA mechanism, arguing that the platforms operate negligently when responding to copyright infringement requirements. And in most of the cases where they manage to block the illegal content, it reappears in other user accounts and in other portals throughout the Internet, making the task of tracking and adjudicating legal responsibility to the actors involved fruitless. [4]

Not surprisingly, OpenSea has failed to contain all cases of copyright infringement, leaving many plagiarism lawsuits that have affected digital artists up in the air. This can put the company in serious trouble, which currently has difficulty exercising stricter controls and requiring verification of its users at the cost of losing market share and sacrificing the advantage of decentralization. In any case, OpenSea will have to face a wave of legal demands that can lead to serious economic and criminal consequences.

Just recently it has been commented on the possibility that the company could lose its legal shield by participating economically in the sale of "stolen" items that violate the copyright of other artists. And the truth is that the OpenSea platform charges a percentage for the sale of NFTs, such as registration and transfer services. That would put almost all platforms involved in NFT trading at risk, which would not fare well in court when accused of facilitating crimes.

Extreme measures for combating "Piracy"

Although DMCA does help to alleviate tensions between plaintiffs and infractors of copyright, it also has shown to be irrelevant in reducing the cases of plagiarism and fraud: It has served more as a dissuasive mechanism than effective protection to defend intellectual property.

For that reason, legislators from U.S. and Europe have been promoted more radical policies oriented to prevent such violations could happening, at any cost. And they will have no qualms about harming Internet companies, which would be accused of facilitating what is considered "Criminal Activity" related to the violation of intellectual property rights.

In June 2021, the European Parliament put into effect a reform to the Copyright Protection statute: under articles 11, 13 and 17 of the Europe Directive on Copyright, member states will require Internet service companies to control the content that users upload to their platforms and transfer on their networks. If they do not do so, they will carry the responsibility of the infractions committed by their users with criminal charges and very high fines.

Additionally, those platforms now will require permission from rights owners to reference their content via hyperlinks. Also, they would be obligated to actively monitor user-generated content to prevent unauthorized appropriation of licensed media. [5]

In parallel, just in December of 2020, the U.S. Congress has approved the CASE Act directive which establishes a "Fast-Track" diligence for easing the litigation on Intellectual Property cases, even for low quantities, and granted to any citizen who demands them.

This new law will be put into effect in the first quarter of 2022 and offers free legal support by a “Copyright Claims Board", an staff of IP specialists in the Copyright Office dedicated to studying the lawsuits and boosting judicial processes related to IP Law enforcement, the kind of legal cases which in normal circumstances would carry very high costs for demandants. [6]

The particularity of the CASE Act is that it does not require the formal registration of copyright works, which opens the door to all kinds of blackmail and judicial opportunism, which many will take advantage of to extort profits at the expense of the companies through false unfounded accusations. [7]

With the recent regulatory framework in place, the future of web-based industries will become dark and uncertain. The task of moderation by publishers and administrators of interactive sites would become unmanageable, and probably the vast majority of blogs and forums on the internet will have to close their operations. [8] Only those corporations with a lot of capital and advanced computing infrastructure could barely subsist under these new rules, and will probably have to exert some lobbying power to legally shield themselves. [9]

The immediate consequence will be that these technological giants adopt proactive measures to prevent the publication of illegitimate content, through the application of automated filters based on Artificial Intelligence. There are doubts about the effectiveness of these technologies to detect the lack of authenticity in digital art and intellectual works. [10] These companies will probably choose to charge their users for the right to express themselves and will place many restrictions on their speech. For this reason, there are fears that it will end up violating freedom of expression in a generalized way. [11]

So, it is worth asking if it is necessary to go to such lengths to defend the rights of authors and artists? To the point of leading the entire world into obscurantism, losing decades of technological advances, shutting down the Internet, limiting free expression, and putting up barriers to innovation. Just to avoid violating any legal right over a certain portion of human creativity?

The scope of the so called "Intellectual Property"

The point is that the limits of "Intellectual Property" are arbitrary, cannot be determined objectively, and aren't based on any universal foundation of ethics. The problem with awarding monopolies over artistic ideas and creations is that they establish a conflictive and contradictory legal regime: They grant authors partial rights to the legitimate property of all persons who inadvertently manifest ideas derived from those creators in their private spheres. The sovereignty of people over their private property in their devices and means of expression is undermined. [12]

We must remember that the foundation of Private Property as an ethical principle constitutes the pillar of Natural Rights, as defined by the philosophers of classical liberalism such as John Locke, David Hume and Adam Smith. The application of the ethics of Private Property has emerged in the development of human societies as a natural mechanism for peaceful coexistence, by avoiding conflicts between individuals over scarce assets and resources. [13]

Moreover, Private Property becomes a vehicle for voluntary cooperation by operating as a means of exchange, where the parties reach a mutually beneficial consensual agreement either through barter or the transfer of rights of use over the property.

In summary, the defense of Private Property is based on a universal ethical principle based on the Justice of Natural Law, fosters respect for the self-determination of individuals, and is the basis for peaceful coexistence among the members of a community.

It is necessary to clarify that Intellectual Property is not the same as Private Property:

The first constitutes an arbitrary right granted by some political authority. It grants an artificial monopoly over public goods (Because when expressing an idea, intellectual work or design, it becomes common heritage when communicated to the public) and its defense corresponds to convenience motivations, appealing to the need to encourage the work of authors and artists by guaranteeing their economic subsistence.

While the second is a foundation of ethics based on Natural Law, it governs in the private sphere, and its defense corresponds to matters of Justice.

Sometimes it is worth making such a clarification and explaining the obvious, in order to have objectivity when dealing with the paradoxes induced by the Intellectual Property laws. In fact, the rights and patents on ideas have been forged as an arbitrary convention in modern times under Utilitarian philosophical principles: They start from a philosophical current of planned economy, which assigns to the government the responsibility of maximizing economic benefits and promoting industrial progress of a nation, by enacting laws that reward innovation and punish plagiarism. [14]

And just as Copyright is based on arbitrary foundations, the jurisprudence and laws that apply to it lack all proportionality and coherence. They usually lead to ridiculous mix-ups and absurd controversies (worthy of an episode of South Park) such as the dispute over the rights to the photograph of "Naruto", the monkey who took a "selfie" and whose image went viral on social networks. The controversy arose over determining who would receive the royalties from the rights to the photograph, where PETA activists allege that the monkey is the one who should be the legitimate author of the photograph and not the photographer who had his camera. [15]

In a Forbes article on the "Naruto" case, Tim Worstall states that copyright royalties must be resolved with a utilitarian approach based on economic incentives (in favor of the photographer), and cannot be treated as a matter of justice to favor the rights of the monkey (And in that case, PETA would claim the economic royalties of the photograph acting on behalf of the monkey). Because the question is what economic motivation would lead a monkey to take pictures? [16]

Copyright is a matter of incentives

If ultimately, the justification for Copyright law is based on guaranteeing economic incentives for intellectual and artistic production, its effectiveness remains in doubt when in reality it ends up limiting the work of artists to create new works. If most of the effort is devoted to reviewing the registry of licensed works and requesting permission from the authors, the intellectual task would become very arduous and costly to the point that the economic benefits obtained from the commercialization of works could not compensate for the effort.

Regarding the actual effectiveness of Intellectual Property laws, Michele Boldrin and David K. Levine have extensively documented cases in which it is evident that such laws actually restrict artistic activity and undermine innovation, contrary to the expectation of the supposed benefits that they should encourage. [17]

On the other hand, large corporations have the legal and financial apparatus to manipulate the system in their favor, often to the detriment of the original authors. In most cases, copyright and patents aren't used to create value in intellectual works, but rather to curb competitors. They constitute more of an arsenal of sabotage and destruction of other people's businesses than instruments to enrich society and commerce.

So, wouldn't it be better to develop alternatives to Intellectual Property, Copyright and Patent laws, focused entirely on solving the economic need of authors and artists?

Lessons from the NFT market

Surprisingly, the NFT market already offers us clues to develop a non-violent solution to the problem of intellectual production. An objective look at its operation reveals that the price dynamics in the market is affected by the authenticity of the works.

Statistically, plagiarized works have very poor sales. Which shows that the market itself can regulate cases of plagiarism without conflicting disputes. Collectors try to invest in authentic works and make sure that the funds do support the original creators. And at the same time, they avoid being victims of fraud when they acquire plagiarized works for fear of causing a loss of property and not being able to sell their digital items at a better price.

Actually, NFT technology already has a mechanism to verify the provenance of artworks by revealing an account identifier that is associated with the original publisher. It is enough for the artist to take credit for having registered his collection as NFT on his official website, notifying his followers of his project, and confirming the code that identifies the collection of minted tokens.

There are guides that teach collectors good practices when investing in NFTs. Practices such as duly studying the artist's career, and his tacit intention to promote his NFT project on his official website. [18] In this way impersonators and swindlers are excluded. The same community of followers of the artist has the power to validate the authenticity of his works.

And in terms of incentives, it is also true that NFTs have economically benefited more artists than those who have supposedly been affected by plagiarism. Many have managed to make massive sales of their works for the first time and get more income than they would get from regular merchandise sales. In addition, collectors have the incentive to acquire NFTs as an investment, obtaining benefits in subsequent sales.

Like all new technology, it is still in an experimental phase and will not be able to prevent some from abusing the system and misleading buyers. But this issue has to be resolved more with a focus on improving the user experience (UX), rather than adopting a punitive scheme that involves disputes with litigation.

In the future, more solutions will be developed that improve the current NFT model and emphasize the relationship that collectors establish with digital content creators. Such solutions would not be based on commercializing digital works but on granting buyers participation in the artist's creative process and giving them the benefit of being part of their community. In later articles we will explore possible implementation mechanisms through the DAOVOTION project.

[1] Harrison Jacobs, The Verge (2022). "THE COUNTERFEIT NFT PROBLEM IS ONLY GETTING WORSE: So artists are joining together to fight back". Available at: https://www.theverge.com/22905295/counterfeit-nft-artist-ripoffs-opensea-deviantart

[2] Jason Kelley, Electronic Frontier Foundation (2020). "Section 230 is Good, Actually". Available at: https://www.eff.org/es/deeplinks/2020/12/section-230-good-actually

[3] Ashley Johnson y Daniel Castro, Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (2021). "Overview of Section 230: What It Is, Why It Was Created, and What It Has Achieved". Available at: https://itif.org/publications/2021/02/22/overview-section-230-what-it-why-it-was-created-and-what-it-has-achieved

[4] Matthew Barblan & Kevin Madigan, George Mason University (2016). "Three Years Later, DMCA Still Just as Broken". Available at: https://cip2.gmu.edu/2016/06/30/three-years-later-dmca-still-just-as-broken/

[5] Comisión Europea (2021). "New EU copyright rules that will benefit creators, businesses and consumers start to apply". Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_21_1807

[6] Jason Kelley, Electronic Frontier Foundation (2020). "The CASE Act Is Just the Beginning of the Next Copyright Battle". Available at: https://www.eff.org/es/deeplinks/2020/12/case-act-hidden-coronavirus-relief-bill-just-beginning-next-copyright-battle

[7] Shiva Stella, Public Knowledge (2019). "Public Knowledge Opposes Copyright Bill Creating Unaccountable “Small-Claims” Court". Available at: https://publicknowledge.org/public-knowledge-opposes-copyright-bill-creating-unaccountable-small-claims-court/

[8] Pablo Romero, Publico (2018). "Alerta: Europa puede cargarse la Wikipedia y los memes con sus normas sobre copyright". Available at: https://www.publico.es/sociedad/internet-alerta-europa-cargarse-wikipedia-memes-normas-copyright.html

[9] Jonathan Greig, TechRepublic (2018) ."EU copyright reform proposal: 3 things businesses need to know". Available at: https://www.techrepublic.com/article/eu-copyright-reform-proposal-3-things-businesses-need-to-know/

[10] Emma J Llanso, SAGE (2020). "No amount of “AI” in content moderation will solve filtering’s prior-restraint problem". Available at: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/2053951720920686

[11] Amélie Pia Heldt (2019). "Upload-Filters: Bypassing Classical Concepts of Censorship?". Available at: https://www.jipitec.eu/issues/jipitec-10-1-2019/4877

[12] Stephan Kinsella. Against Intellectual Property. Ludwig von Mises Institute. 2008. ISBN 978-1-933550-32-9.

[13] George H. Smith (2015). "John Locke: The justification of Private Property". Available at: https://www.libertarianism.org/columns/john-locke-justification-private-property

[14] Caterina Sganga, Edward Elgar Publishing (2018)."Propertizing European Copyright: History, Challenges and Opportunities" (Chapter 1: The theoretical framework of copyright propertization). Available at: https://www.elgaronline.com/view/9781786430403/09_chapter1.xhtml

[15] Wikipedia, "Monkey selfie copyright dispute". Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monkey_selfie_copyright_dispute

[16] Tim Worstall, Forbes (2016). "Copyright Is About Incentives To Innovation, Not Justice: What Incentive Does Naruto Need?" Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/timworstall/2016/01/07/copyright-is-about-incentives-to-innovation-not-justice-what-incentive-does-naruto-need/?sh=3891148e27c3

[17] Boldrin, M. y D. K. Levine [2004], “2003 Lawrence Klein Lecture: The Case Against Intellectual Monopoly”, International Economic Review 45: 327-350.

[18] AIRNFTS. "How to Validate the Authencity of an NFT". Available at: https://www.airnfts.com/post/how-to-validate-the-authencity-of-an-nft